Our Blog

There is no doubt that the art auction world is a high stakes one. This is not a surprise, especially considering the selling price of pieces in recent auctions. In a March 2018 auction, Pablo Picasso’s “La Dormeuse” was sold at Phillips’s for £41.9m, while Leonardo da Vinci’s “Salvator Mundi” sold in November 2017 for a record-shattering $450m (£341m). The buyer’s ease of mind – and credibility of the painting’s source – is of the utmost importance in transactions like these. So, what happens when the authenticity of an art work is questioned?

Slander of title, or a false denial of a work’s authenticity, can result in serious consequences. Incorrectly lowering the reputation of an artwork can leave you liable for damages. This principle is famously exemplified in a 1929 United States case that set a precedent for slander of title.

The case regarded a supposed da Vinci: “La Belle Ferronniere.” The painting belonged to Andree Hahn, a gift from her aunt whose grandfather bought it in 1847. Hahn arranged to sell the painting to the Kansas City Art Institute for $250,000, which is about $3,600,000 today. However, this sale didn’t go as smoothly as she would have hoped.

Hearing about the sale, Sir Joseph Duveen, a highly influential art dealer, declared that this da Vinci was a fake. He insisted the original piece was currently in the Louvre, and da Vinci never made multiples of his own pieces.

The problem was, Duveen hadn’t seen Hahn’s “La Belle Ferronniere” before making this accusation. His slander cost Hahn the sale – as the Kansas City Art Institute rescinded their offer upon this doubt, costing Hahn a great sum of money.

In retaliation, Hahn took Duveen to court over the slander of title. This proved to be a lengthy legal process, and one that was very widely reported. In the end, the jury could not unanimously decide if the painting was real or not – and, in turn, prove whether Duveen’s comments were false. Duveen eventually paid Hahn a $60,000 settlement plus court costs to avoid going to retrial.

This case has impacted how we look at slander of title in today’s art world. Since Hahn v Duveen, experts have remained cautious about offering statements on a work’s authenticity. One slip could find them entangled in lengthy slander or disparagement litigation.

Interestingly, a 1993 examination proved “La Belle Ferronniere” to not be an original da Vinci. It still proved to be valuable though, selling for $1.5 million at a 2010 Sotheby’s auction.

Regardless of the piece’s authenticity, Hahn v Duveen set a precedent for how vital refraining from wrongly attacking the reputation of an artwork can be. Reputation protection should be at the forefront of one’s mind in any art transaction. If not, the cost may be great.

Daniel Taylor of Taylor Hampton solicitors (experts at defamation and reputation management.)

There are few in the art world who haven’t heard of the Beltracci forgery scandal, where Wolfgang and Helene Beltracci were charged and convicted of selling 14 forged paintings (the actual number of forgeries is still unknown). High profile cases like this boast the drama and excitement that comes with the trial of a master forger. However, there is always collateral damage when sales of forgeries occur.

In the case of the Beltracci trial, art expert Werner Spies, who had no knowledge of the fraud, was unwittingly caught up in the affair. Werner Spies originally claimed an alleged Max Ernst piece, actually painted by Beltracci called “Earthquake,” was authentic and should be included in Ernst’s catalogue raisonné. Having been informed by the police that the painting might be fake, investigations showed that the purported work by Ernst contained pigments used after the paintings was supposed to have been painted.

In 2011 The Monte Carlo Art Company sued Werner Spies for negligence in France after buying the painting and selling it through Sotheby’s in a New York auction for $1.14 million. They bought the piece under the assumption that it was an original Max Ernst, and subsequently had to refund the buyer.

On appeal in 2015, it was decided that an opinion given by an expert in the course of an auction sale, needed to be distinguished in respect of an author of a catalogue raisonné.

An expert could not be requested to proceed with a scientific analysis of every painting in a catalogue raisonné and cannot be held responsible in the same manner as an expert giving an authenticity opinion in the context of a sale. Werner Spies was found not to have been negligent in his actions.

While Werner Spies is an example of an individual brought to court over this tort, auction houses can also get sued for negligence. Take, for example, the case of Dickson v Christie’s in 2010.

David Dickson and Susan Priestley sold “Salome with the Head of St John the Baptist” for £8,000 after an assessment by Christie’s determined the painting was from the school of Titian, and not the artist himself. However, Sotheby’s later sold the painting having assessed it as an original. It was put up for auction with a starting price of $4 million. Dickson and Priestley claimed Christie’s didn’t do the proper research in determining the painting’s correct origin and selling price. However, this case settled before trial.

The more recent Thwaytes v Sotheby’s saw the auction house accused of negligence and breach of contract. Mr. Thwaytes sold Caravaggio’s “The Cardsharps” for £42,000 after Sotheby’s x-ray analysis assessed the painting as a 17th century copy. After the sale, Sir Denis Mahon made public that he believed the painting to be painted by Caravaggio himself. After this, the painting was shown at exhibitions and was at one point insured for £10 million.

Thwaytes brought legal action against Sotheby’s, claiming they were negligent in their assessment since they didn’t come to the same conclusion. It was determined that Sotheby’s was not negligent, as merely because an auction house acts in a certain way that does not automatically mean that it has been negligent. Sotheby’s were entitled to rely on their expertise and connoisseurship by considering first and foremost its quality. They reasonably came to the view, on the basis of what they saw, that the quality of the painting was not sufficiently high to indicate it was a Caravaggio.

While auction houses are rarely found guilty in cases such as these, they are still dragged through lengthy legal battles to prove their work was sufficient. The risk of legal action after misattributing works is so great that many have decided authentication isn’t worth the risk. For instance, London’s Courtauld Institute of Art cancelled a forum discussing works by Francis Bacon to avoid potential legal action. Additionally, The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts has stopped authenticating works altogether.

With the constant threat of litigation in the air, negligence seems to always weigh on art experts’ minds. Not only can a negligence case have a heavy cost of time and money, it can also threaten one’s reputation. That can have with permanent consequences.

A last word to Werner Spies referred to earlier. In an interview with Stern magazine, he said, “how could I bear the knowledge that I was taken in [by the fake Ernst]? The loss of my reputation! It made me think that I should say good-bye to this world.” While the art world can come with high stakes, with the correct due diligence, one can make sure that one’s reputation stays protected and insured.

Daniel Taylor of Taylor Hampton Solicitors (expert solicitors at defamation and reputation management.)

Will Romania’s national treasure, “The Wisdom of Earth” by Constantin Brancusi be lost in election politics?

What started as an exciting cultural campaign to save a stunning early sculpture by Constantin Brancusi (one of the most important sculptors of the 20th Century) has turned into a political fiasco.“

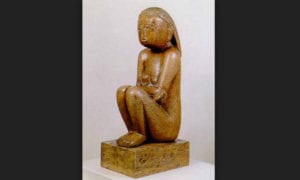

Cumintenia Pamantului” or “The Wisdom of Earth” depicts a female nude, made in limestone and is typical ofthe sculptor’s timeless style. Drawing on the mythical, the relationship between heaven and earth and the ancient, the work strongly resembles primitive art, in particular the ancient heritage of Romania – see The Thinker and the Sitting Woman that were found in Romania and are around 7,000 years old from the Hamangia culture. (The Thinker of Cernavoda and the Sitting Woman, 5,000 BCE Terracotta Sculpture, National Museum of Romania.)

This artwork’s provenance has not been without controversy. The piece was originally bought by a friend of Brancusi, Gheorghe Romascu, who purchased it in 1911 from the artist. Then in 1957, the artwork was seized by the Communist government and it took an extremely long legal case for the work to be restored to Romascu’s heirs in 2012.

The desire to keep the cultural treasure within Romania is marked by the fact that very few works by Brancusi are in Romania, as the sculptor left to live in Paris when he was 28 years old.

The Government, keen to secure the work, was faced with having to raise €11 million to buy the artwork from the Romascu family heirs to try to keep it in Romania. Unable to purchase the work outright with public funds, the government proposed to contribute €5 Million to the purchase and through a fundraising campaign called “Brancusi is mine” they hoped to raise the rest of the funds from voluntary donations from individuals and companies.

A deadline was set for September 2016, but the amount raised from the public fell woefully short, amounting to just over €1 million.

In October, the Government, still keen to secure the work, passed an emergency ordinance to purchase the work and to look for a financial mechanism to cover the shortfall. The Government then looked to Parliament to approve the acquisition, but this approval was not given.

According to the Romania Insider, in the lead up to the Presidential elections, the issue of the public fundraising campaign and the government pledge to bridge the gap from the budget had received virulent public criticism. It further became a battleground for criticism and reprisals as the former Romanian PM Dacian Ciolos now faces a complaint filed at the National Anti-corruption Directorate by PRU leaders. Ciolos is accused of an abuse of power and deceit for the way in which his

cabinet handled the public fundraising campaign. The claim is that the price the government agreed to pay far exceeded its value. PRU president Bogdan Diconu further said, “The Ciolos Government has spent €11 million from the Romanians’ money for a work of art that was part of the national heritage anyway, and couldn’t have been taken out of the country.”

A law was passed that stated that if the Romanian state did not acquire the sculpture before 21st October, those who had donated money could ask for their money back.

After a meeting with the new Government to understand whether the Ministry of Culture still wanted to purchase the work, according to the Romania Insider, it now seems that the sculpture’s owners may decide to sell the artwork by auction.

This artwork has had quite a journey and it will be interesting to see whether it does come up in auction and what price is realised for this masterpiece: watch this space.

Jessica Franses

Vienna Philharmonic returns priceless artwork to heirs of expropriated owner Austria has recently been the focus of an investigation looking into the alleged theft of an artwork during World War II.

The canvas in question was painted in 1883 by renowned French Neo-Impressionist master, Paul Signac. The work is entitled ‘Port-en-Bessin’ has become one of the artist’s more familiar pieces since the discovery of its unhappy past and associated restitution issues.

The work, valued at over $500,000, was originally owned by Marcel Koch.

By 1940, however, it had been presented to the Austrian Philharmonic Orchestra by an Austrian national named Roman Loos, who at that time was serving in France as the Secret Police’s Head and Chief.

Artnet News reports that the work was passed to the Austrian Philharmonic Orchestra ‘in exchange for a series of performances’, following its illegal expropriation from Mr Koch.

The decision to trace the history of this fantastic work was taken in 2013 by the

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra’s Director, Mr Clemens Hellsberg.

The task of confirming the work’s hazy provenance in 2013 was allocated to art historian Sophie Lillie. Ms Lillie had to search broadly to find the rightful owners as Mr Koch sadly passed away in 1999 leaving no direct descendent.

Following investigation, the work is to be given to the heirs of Koch’s estate who will, upon receipt of the piece, possess a truly fantastic work of neo-impressionist art.

Returning the work to its proper legal owner has been of vital importance for this historic institution.

Recalled in an article by Artnet News, Mr. Clemens Hellsberg is said to have told ORF, “for years we have strived to examine the past of the Vienna Philharmonic, and we are taking responsibility to make up for historical injustice.”

Reports suggest that the investigation into the history of the artwork has, in fact, been ongoing since the 1980s and is an indication of the difficulties that can beset recovery cases.

The painting’s return to Koch’s heirs will also end a long running restitution case, which has been ongoing since the Philharmonic Orchestra initially identified Koch’s heirs and announced a desire to return the painting in April 2014. It is reported that, according to the Austrian daily newspaper Profil, five heirs have reportedly chosen to sell the artwork through a Parisian auction house.

In recent years, many cases such as this one have come to trial all over the world as relatives of individuals whose property was stolen by Nazi forces are claiming their rightful inheritance.

In an attempt to reunite original owners with their priceless artworks, new institutions, companies and research databases, together with governmental groups, have developed to fill this void. Better research mechanisms, legal developments and a greater will to restore works to their rightful owners in part explain the seeming rise in the number of restitution cases over the past years.

Any individual or company looking to purchase art should always pay full attention to the work’s provenance. Although in some jurisdictions, such as England and Wales, rules on the limitation of actions may in some cases make it difficult for heirs of former owners to bring claims many years after a theft. However, owning a work of art that turns out to have been looted by the Nazis without returning it to its former owner’s heirs can also be damaging to an institution’s reputation quite aside from any legal claim.

With numerous potential pitfalls that can arise if there is a potential issue regarding ownership or history, a full and comprehensive survey of a work’s history and provenance is of paramount importance.

A history of having been looted by the Nazis is not the only area that could give rise to a potential recovery claim or reputational damage, and where insufficient details are provided about an artwork’s history, there remains the potential that there could be other legal or beneficial interests in an artwork, reducing or even eliminating entirely its value to a purchaser.

At the ADDG, through Artive, our specialist service provider for title claims checks and Art Recovery, our specialist service provider for assisting with recovery of stolen artworks, we can provide comprehensive assistance to clients before artworks are sold or purchased to deal with any potential restitution or title claims issues before they become a serious – and potentially expensive – problem.

To find out more about title checks, restitution and provenance research, please contact us at: [email protected] and on 07460 352 939.

If you are interested in understanding more on this fascinating topic, please see the following:

– Restitution alert – Dutch website launched to reunite looted art works with lawful owners.

– Wind of Change – Part 1: Restitution, France” here – http://jessicafranses.com/wind-change-part-1-restitution-france).

Jessica Franses

French couple found guilty of theft as unparalleled number of Pablo Picasso works found in their possession.

Aix-en-Provence has served as the location of an important trial, one which has gripped the art world for over two years. Pierre Le Guennec, now 77 years old, was master painter Pablo Picasso’s electrician for over forty years.

A trial was held at Aix-on-Provence’s Court of Appeal, where the court heard that Mr Le Guennec had deliberately been hiding huge volumes of the artist’s works during his visits to his home throughout this period.

Having successfully hidden the works, Le Guennec subsequently removed them from the premises after Picasso’s death, with the intent of concealing them from his heirs and the inevitable inventory of his final body of work.

On the conclusion of the case and in his final judgement of 16 December 2016, the judge found Pierre Le Guennec’s wife, Danielle, also guilty. Danielle ‘received the same penalty’ as her husband and their two year suspended sentence was upheld, the Art Newspaper recalls.

So what did Le Guennec steal? The answer is an enormous volume of art – both in number and monetary value.

271 works were stolen and include unknown important collaged pieces from his Cubist era, paintings, drawings and a number of sketch books, all originals and all extraordinarily rare.

Experts reviewing the collection, confirming attribution and provenance, have confirmed that none of the pieces found were either signed or catalogued.

In essence, a large new body of work has been discovered and these stolen artworks could have gone undetected as they had been hidden from the Picasso heirs for over 4 decades.

The Art Newspaper, in an article dating from 16 December 2016, confirmed that the losses are in the region of ‘€70m to €80m’.

The works, ‘dated from between 1900 to 1930… [and] include portraits of family and friends, such as his first wife Olga, Guillaume Apollinaire and Max Jacob, two sketchbooks as well as extremely rare and precious Cubist collages.’

Both Danielle and Pierre Le Guennac had provided a number of conflicting stories as to how they came to posses such an enormous body of art. It was claimed at one point that they had been given the works by Picasso himself, then it was claimed that Picasso’s wife Jacqueline had given them the artworks in the presence of Picasso and then it was later asserted that Jacqueline had given to Le Guennac the artworks as a reward for having asked him to conceal 16 or 17 rubbish bags filled with artworks, to avoid them being included in Picasso’s inventory of works for succession reasons.

Ultimately, the Art Newspaper reports, ‘In the final verdict, the judge described the Le Guennecs’ story as an “implausible and whimsical tale”,’ with no real evidence of how they came to own over 250 masterpieces of 20th century art.

Picasso is widely regarded to be one of the most successful and revered artists ever to have lived. This revelation has shaken the art world and serves as a warning to anyone managing the estates of the world’s best and most celebrated artists.

Theft from an artists’ estate is not an unusual phenomenon, particularly where an artist has been prolific. For this reason, professional management, inventories and systems, while a large undertaking, are necessary where an artist has produced valuable work and a legacy for their descendants.

According to the Art Newspaper article, what emerged from the case is that the Le Guennecs were closely connected with the late chauffeur of Picasso, a man called Maurice Bresnu. Through the criminal investigation it emerged that Bresnu had stolen around 500-600 drawings by Picasso and had sold most of them.

The risks of acquiring stolen artworks are very real: anyone who had purchased a work from Le Guennac within the last six years would probably, under English law at least, have to return it to Picasso’s estate with the only hope of compensation being from Le Guennac himself, who would be unlikely to have the funds to satisfy any claim. Most people think that it will not happen to them; however, at the ADDG we are aware of countless examples of this sort of activity and hope that our resource will raise awareness of this issue and how to avoid it.

At the ADDG, we have specialist service providers who can assist with the recovery of stolen artworks and service providers who can assist with all the necessary due diligence checks before any art purchase is made.

Detailed provenance research and title checks on the artworks and background checks on the seller should help mitigate against the potential risks of acquiring stolen artworks. The risks attached to acquiring stolen artwork are that one may not obtain good legal title or rights to own that artwork and could become embroiled in a legal dispute over ownership and criminal investigation; all of which are potentially damaging financially and potentially harmful to one’s reputation.

If you have enquiries or concerns about these issues, please do not hesitate to contact us at [email protected] or on 07460 352 939.

Jessica Franses

Restitution alert – Dutch website launched to reunite looted art works with lawful owners.

During the atrocities of the Second World War, many artworks were seized from innocent individuals and families by the Nazis. Artworks were either stolen when families fled their homes or sold in forced sales against their owners’ wishes at vastly reduced prices.

There are still many looted works in circulation and whose owners are still unidentified. Some estimate that as many as over 100,000 artworks have not yet been returned to their rightful owners.

Not all of these works are detected in public sales and many works are sold privately where people are completely unaware of the Nazis looted history to the works. Some of these works remain undetected or improperly investigated in museum collections, too.

Identifying title to the works is often a highly complicated process, usually down to a lack of access to the records, which may be lost or even have become separated from the work. This lack of information makes it extremely hard for prospective heirs to locate lost works and to prove ownership. Some heirs are completely unaware that their possessions are in existence.

Some works remain in state collections and in some circumstances the collections administrators still cannot identify owners. An example of this is the Nederlands Kunstbezit collection that contains approximately 4,700 art objects. This collection is what remains of the artworks recuperated from Germany after World War II and is managed by the Dutch State.

Against this backdrop, there has recently been the launch of a new Dutch website called ‘Herkomst Gezocht’ or in English, ‘Origins Unknown’.

To visit the website please click here – http://www.herkomstgezocht.nl/nl/

The website seeks to extend efforts to reunite artworks with the descendants of their original owners by allowing users of the website the ability to track down pieces which were unlawfully apprehended and access useful archival material.

Over 14,000 documents have now been uploaded to the website, with reports or photographs being made available, each relating to lost or stolen art works.

The centralising of information should enable individuals or families to search more effectively for their lost heirlooms.

The website service aims to allow individuals to search promptly and extensively, cutting out the need to filter through documentation by hand, as had been the practice for previous generations.

Rudi Ekkart is an art expert and is in support of this programme. Ekkart told NOS that the beauty of Herkomst Gezocht is that, “now everything is on the internet and you can use search terms,” to locate art. This has significantly increased the chances for success for those searching, as well as much reducing time spent doing so.

“It’s not just interesting for researchers and art dealers”, said Ekkart. ‘”Anyone can see if their family’s name is in it. In many families people didn’t talk about the war, so people often don’t know if grandma or grandpa reported missing works of art.”

Around half of the total works on the list are paintings, while another 1,000 items are sketches. There are also items of furniture, ceramics, silver and musical instruments.

On the website it is stated that Origins Unknown Agency (BHG) was founded in 1998, commissioned by the Dutch government to conduct provenance research into the state art collection (the NK collection). In addition, BHG handles all kinds of requests for information related to looted art.

Also on the website it is stated that BHG since January 2015 has sought recovery of around 15,000 lost artworks that were obtained by the Germans during the occupation of the Netherlands and were not recovered by the Allies after the Second World War. BHG has been digitising claims for these lost works and these claims are part of the Stichting Nederlandsch Kunstbezit (SNK) archive. SNK had been tasked with recovering these lost works in Germany and overseas.

The website has highlighted a particularly difficult aspect of examining these types of restitution issues, being that “not every work of art that has fallen during World War II as a result of coercion from the possession of the original owner has subsequently ended up in Germany.” The search for reuniting owners and artworks is a truly global one.

At the ADDG, our service provider Artive helps to research the lost or stolen art databases and checks whether title to artworks is obfuscated by potential restitution claims or other third party interests. They provide detailed reports on title checks. Our service provider Art Recovery International is an expert company that deals with the recovery process of historically looted or stolen art and our service provider Vitruvian Arts Consultancy Ltd. provides experts and provenance researchers to ensure an artwork is thoroughly investigated before sale. Members of 36 Art are barristers who have conducted restitution cases.

For any assistance with any potential restitution enquiries please do not hesitate to contact us at [email protected] or on 07460 352 939.

At ADDG we welcome the developments in the field of restitution.

A more modern approach by museums, a better developed legal landscape and a shifting global attitude towards restitution cases has led to some very real and positive developments in this area, one where identifying the provenance of and gaining clarity on who actually owned the artwork historically is becoming a matter of greater significance.

(For more about this issue see this blog article on “Wind of Change – Part 1: Restitution, France” here – http://jessicafranses.com/wind-change-part-1-restitution-france).

Watch this space for more updates on restitution.

Jessica Franses

“Well well, didn’t that do well – I am off for a pint.”

That was the response to the Auctioneer (as reported in the Mirror) of the happy purchaser who attained a Chinese vase that made 150 times its auction estimate at a sale at Auctioneers Lawrences of Crewkerne, Somerset.

Everyone loves a discovery in the art market and “sleepers” (works that have not been correctly attributed or priced at auction that go on to be worth vastly more than the pre-sale estimate and selling price) often attract excitable press coverage.

This colourful Chinese Tibetan Temple Vase stands a little over 25cm in height.

The Antiques Trade Gazette (ATG) described it as “finely decorated in famille rose enamels with the Bajixiang, the Eight Buddhist Emblems, divided by lotus heads and scrolls.”

Most importantly, the vase has the iron red six character seal for the fifth Quing Emperor Jaiqing (1796-1820) on the base of the vase.

Vases such as this were used during the reign of the Emperor Qianlong but this vessel carries a seal for his imperial successor.

Imperial vessels are highly prized and this explains the high level of interest in this work.

In this case, the auctioneer, Neil Grenyer, believed the work to be a 20th Century copy, an example stemming from the Republican period, which began in 1912 and therefore gave a pre-sale estimate of £1,200 to £1,500. It seemed the Auctioneer took a cautious view and was unconvinced that it was an original.

According to news reports, the exact provenance of the work is unknown. The vendors, two brothers from Wiltshire inherited the vase 30 or 40 years ago when their grandparents died and since then it had rested on a mantelpiece at one of their homes. It is understood that their ancestors purportedly brought it back from Shanghai where its owner had been working as a solicitor and may have acquired it around 1910 or 1920.

On the day of the auction on 19th January 2017, there was intense competition for this porcelain work. Telephone biding for this work quickly drove the price up to above £200,000 before the bidders in the room even gained a chance to participate such was the desire for the work.

According to the Mirror, when bidding reached £240,000, there were still four bidders in contention – three on the telephone and one online.

Clearly the bidders may have believed the work to be an original Imperial vase after all.

According to the Antiques Gazette the bidding finally came down to a contest between a prominent Hong Kong dealership and a well-known London dealer.

The hammer fell on an incredible £305,000 and everyone watched in amazement.

This was also a great surprise for the Sellers.

Whether or not the auctioneer has wrongly attributed the work as a late copy is a matter for debate by experts and we may never know for sure.

According to Lawrences, they have got it right and no one has come forward and confirmed the dating of the work to be different to their description.

The sale of this vase is, however, another example in a long line of works sold at auction for prices far exceeding their pre-sale estimates. From ornate china plates, to antique ewers to intricately set wooden cabinets, the list of these so called ‘sleepers’ is expanding.

Whilst sleepers maybe exciting news for buyers (as they represent a find), they can sometimes be less of a comfort to sellers, who may have not appreciated the true worth of their artwork/s.

At the ADDG, our team help sellers to obtain pre-sale valuations, pre-sale expert opinions and assist with the sales process at auction and through private treaty sales.

We help sellers and buyers undertake due diligence pre-sale and encourage parties to take an informed approach before sales are conducted and purchases are made.

Please watch this space for news of any future sleeper news stories.